Rocky Path to Reparations

Gov. Gavin Newsom gave Indigenous Peoples of California an apology and a promise. Now they want action.

In 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an apology to the Indigenous Peoples of California for the genocide that was formative to the state’s creation.

While some of California's Native Peoples appreciate the gesture, others worry it is an attempt by the state to sweep their historical and present-day experiences under the rug.

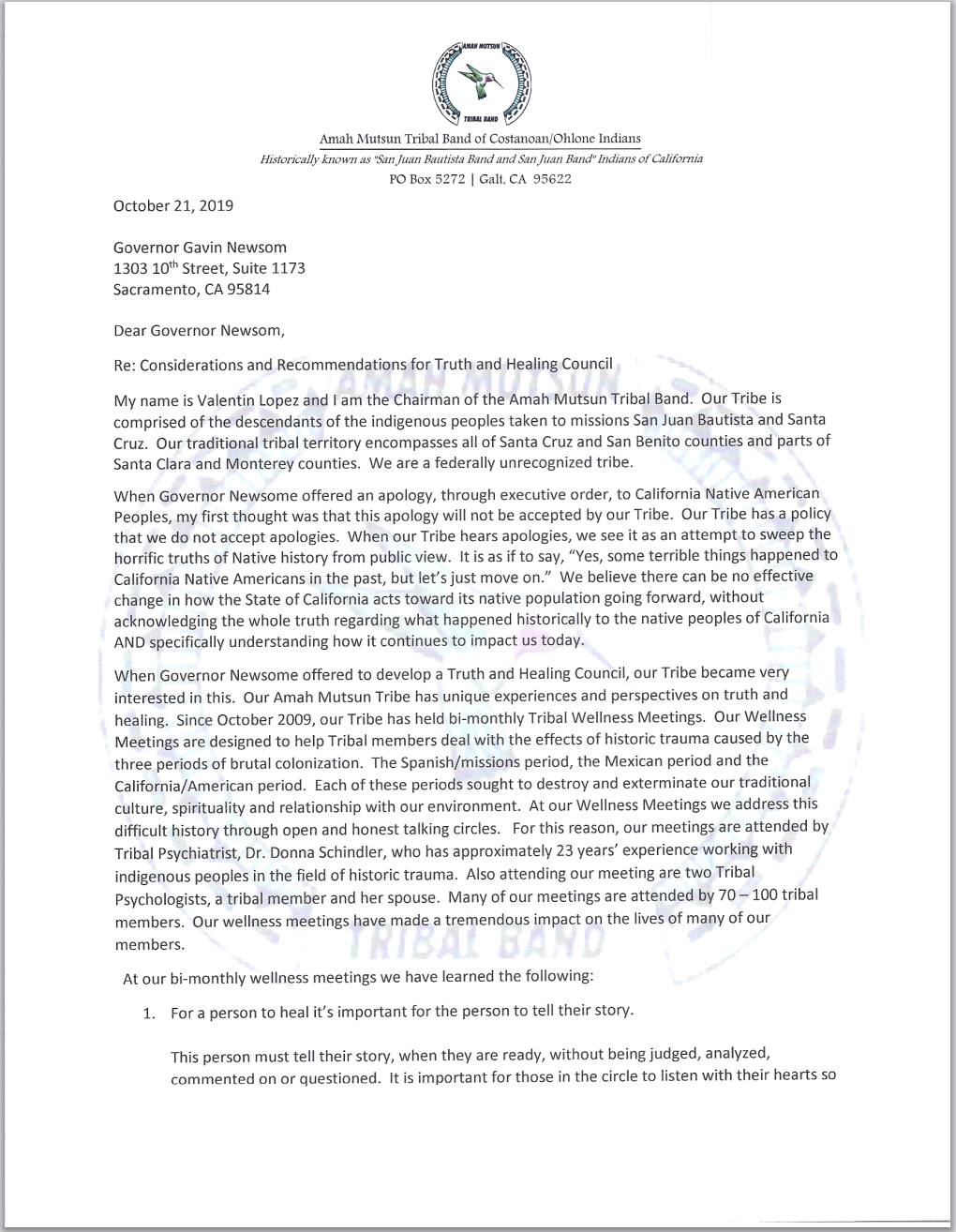

The Tribal Chairman Valentin Lopez, of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, rejected the governor's apology in an open letter.

"Our Tribe has a policy that we do not accept apologies,” Lopez wrote.

“When our Tribe hears apologies, we see it as an attempt to sweep the horrific truths of Native history from public view. It is as if to say, “Yes some terrible things happened to California Native Americans in the past, but let's move on.”

In addition to the public apology, Newsom issued Executive Order N-15-19 which established the California Truth and Healing Council.

The purpose of the council is to "bear witness to, record, examine existing documentation of, and receive California Native American narratives regarding the historical relationship between the State of California and California Native Americans in order to clarify the historical record of such relationship in the spirit of truth and healing."

The Truth and Healing Council will operate for five years. It will consider a plan for reparations, and the council will conclude with a final report by January 2025.

Christina Snider, Tribal Advisor to Newsom and Executive Secretary of the Native American Heritage Commission, is leading the endeavor. Snider is an enrolled member of the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians.

Snider facilitated the first Truth and Healing Council webinar on October 14, 2020. The webinar covered an overview of the draft charter and the voting member nominations process.

Prior to the selection of council members, Chief Caleen Sisk of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe said she was concerned that the endeavor would be similar to, what she called, previous “fact-finding mission” initiatives which have been conducted. She spoke of these concerns during the October 29 meeting facilitated by Snider.

“The truth and reconciliation is like, a nice gesture. But if we're going to create just another report, that's going take another 10 years to point at it again, …” she said.

“Is it a real functional, can take-action kind of committee or commission? Do we have access to change anything at the time, or are we just doing this report-gathering educational information, trying to change colleges, trying to tell the story, but healing only comes when there's justice. And if there's no justice in this, there's not going to be very much healing happening.”

Sisk responded to an email request saying “We don’t need another report and hope for education to resolve some issues, some day.”

Chief Caleen Sisk of the Winnemem Wintu tribe now holds the Truth and Healing Council’s Non-Federally Recognized Tribal seat for the Eastern region.

The voting members of the council were announced on December 2, 2020.

Chairman Kenneth Kahn (Chumash)

Central Region

Kouslaa Kessler-Mata (Chumash)

Central Region

Chairman Mark Macarro (Luiseño)

Central Region

Anthony Burris (Miwok)

Eastern Region

Chairman Neil Peyron (Yokut)

Eastern Region

Chief Caleen Sisk (Wintu)

Eastern Region

Chairman Isaac Bojorquez (Ohlone)

Northern Region

Council member Joan Harper (Pomo/Coast Miwok)

Northern Region

Vice Chairman Frankie Myers (Yurok)

Northern Region

Chairwoman Angela Elliott-Santos (Kumeyaay)

Southern Region

Vice Chairwoman Tishmall Turner (Luiseño)

(Kumeyaay)Representatives were selected by Snider through a process of tribal recommendations.

The process was announced and explained in the October 14 webinar and tribal representative recommendations were due on November 13.

The due date was initially November 1, 2020. It was changed after community members pushed for more time during the Oct 14 meeting.

At the time of publication the Non-Federally recognized San Diego / Imperial seat remains vacant.

Alternates

Southern alternate: Robert Phelps (Kumeyaay)

Northern alternate: Councilmember Joseph Giovannetti (Tolowa)

Eastern alternate: Chairman Anthony Roberts (Patwin)

Central alternate: Council member Alexis Manzano (Serrano)

Maura Sullivan is a member of the Coastal Band of Chumash Nation.

Sullivan is a PhD student in Linguistics, a language revivalist and activist. She said her education and professional experience “informs my research outside my community, my research within my community and how I can articulate these systems of power that are extractive.”

“When you do a project, you really have to look at: Do people want this,” Sullivan said. “That's what I really wonder - who asked for this? Did this truly come from an ask from the various California Indian communities, the survivors, the descendants of the survivors of these atrocities? And it felt very forced upon.”

Representation of Non-Federally Recognized Tribes

Jen Olivares is a theatre arts professional and a member of the Acjachemen Nation (The Juaneño Band of Mission Indians.) Olivares's gratitude was mixed with concern. She lamented on what she described as the inter-community impacts the governor’s executive order appears to be creating.

“I felt appreciative of Newsom and company, … but I knew it would cause rifts in the community and communities,” Olivares said. “And I knew that it was obviously too little, too late.”

The Juaneño Band of Mission Indians is just one of many non-federally recognized tribes of California. Olivares said this helps her understand the complicated history of federal recognition.

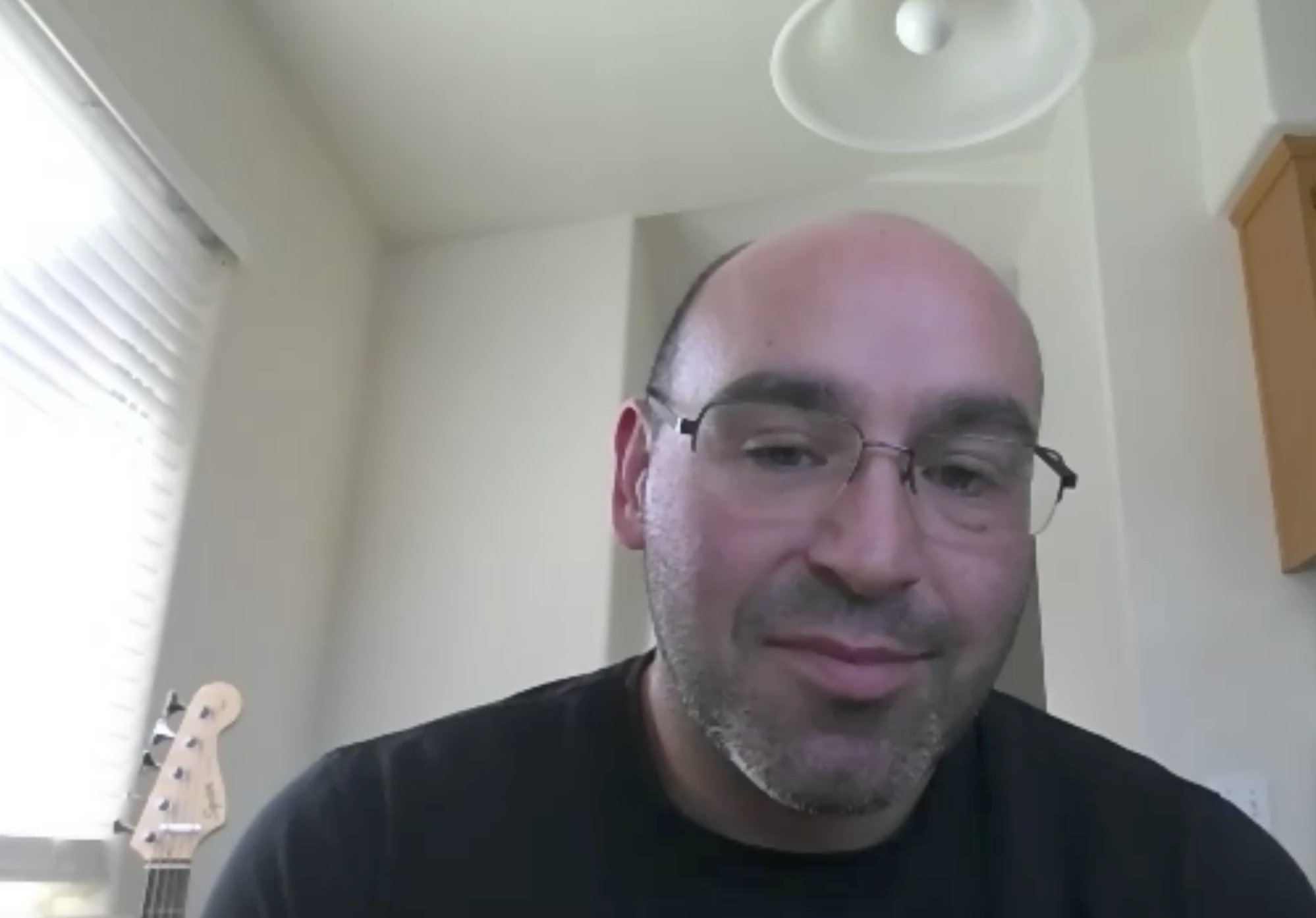

Paul Steward on the history of federal acknowledgement

Federal acknowledgement isn't just a financial matter

When a tribal nation is acknowledged federally that have legal sovereignty which means they gain a nation-to-nation governmental relationship with the United States and a right to self-govern internally.

The Council’s structure permits each region two representatives from federally recognized Tribes and one from non-federally recognized tribes.

Olivares charges that this ratio discriminates against many tribes.

“Oh, this tribe that's not federally recognized, they must be a little bit less legit. So let's just give them a little less of a voice in this region,” she said. “When a lot of the time reasons that tribes are not recognized, is because of the complications of calculated erasure and genocide.”

The charter was put to vote at the first official meeting with voting members.

Before voting to solidify the structure of the Truth and Healing Council, Sisk brought up the charter’s absence of plans for addressing disenrollment and the issue of non-federally recognized tribes.

Snider responded that “disenrollment is not under the purview of the state and I don’t think we feel comfortable with that being something that is formally undertaken by this council in the charter, at least.”

View the conversation in the video to the right. ->

The charter passed unanimously.

What are California's American Indians asking for?

Physical gestures

Return of ancestral lands and physical gestures are a vital part of reparations and healing for many Indigenous Peoples. From the U.S. - Mexico Border Wall's destruction of sacred Kumeyaay land, to the Shasta and Klamath river dams, Indigenous Peoples of California are asking for the right to live on and steward their homelands, protect their sacred sites and have a say in the conservation of their lands.

Hope For Better Education

Improved education about the Indigenous Peoples of California past and present is one thing that California American Indians say they are holding out hope for, though some more than others.

.jpg)

Paul Steward is a member of the Elem Indian Colony in Clearlake Oaks and is a lecturer of Survey of Native California at SF State.

He sees truthful education about California’s Native Peoples as a pathway to equity.

“I would like the real history to be known. The truth, the facts,” he said. “Then, if somebody tells me, … ‘Why are we doing this? Why are we doing nice things for Native American people?’ … We can start to get facts, records and calculations and argue.”

Throughout reporting this story some government materials such as recordings of meetings and public comment may not have been recorded and were unable to be produced by the governor's Office of the Tribal Advisor. Requests for further comment and interview have been requested via through multiple avenues including during public comment on December 4, 2020. Requests were not answered by date of publication.